By Doug Stephens

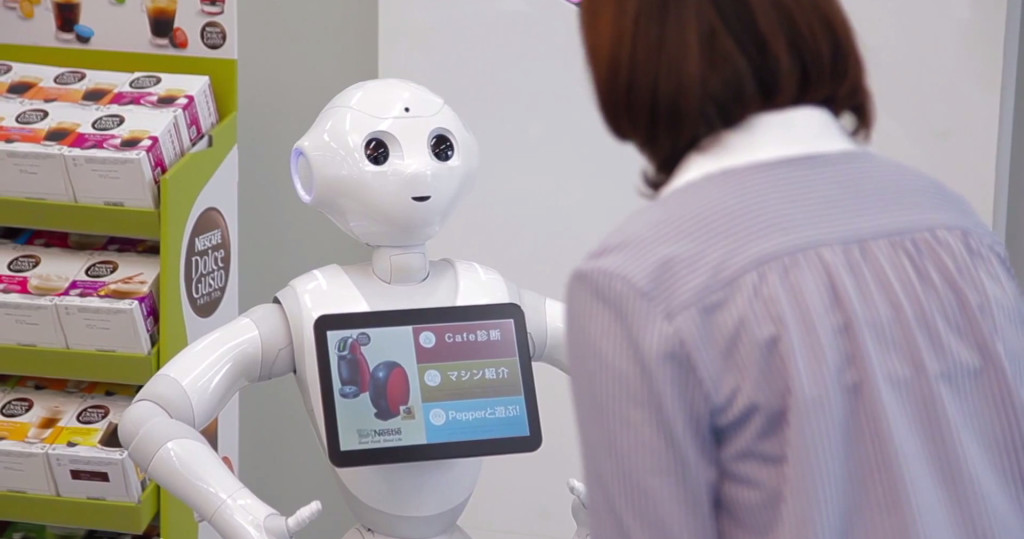

In my 2013 post, Ten Trends to Watch for in 2014, I said this would be the year we would hear much more about technologies such as artificial intelligence and robotics and their potential to replace retail service workers. So, it came as little surprise that U.S. home improvement chain Lowe’s recently announced a test of robots in its Orchard Supply Hardware store in San Jose California. The robots, called OSHbots, are programmed to speak multiple languages, greet customers at the door, field product inquiries and escort shoppers to the exact in-store location of the items they’re looking for. In addition, the OSHbots can also provide additional product information and instruction via video screen interfaces as well as access real-time on-hand inventory information. And all without ever taking a lunch break, a sick day or even a paycheck!

[youtube]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sp9176vm7Co[/youtube]

And, if you’re among those who believe that our innate understanding of human emotion is what safeguards us humans from obsolescence at the hands of technology, it’s important to know that tech company IPSoft has recently announced the release of a virtual customer service platform called Amelia. Amelia not only processes natural speech but also detects emotion in the voice of the customer. This enables Amelia to tailor not only the information delivered but also promises that it will be delivered in a contextually and emotionally sensitive manner.

In combination, these two things – advanced robotics and deep artificial intelligence, make an extremely powerful combination; robotics tirelessly stands at the customers’ beck and call while artificial intelligence accurately retrieves the information they desire, in a manner that suits the context of the query and even the customer’s mood!

Is this the end of people?

It stands to reason that companies like Walmart will be watching such technologies with great interest. After all, consider that they employ more than 1.3 million associates in over 4000 U.S. stores. The potential cost savings from technologizing even a percentage of that sales force would be astronomical. And Walmart is not alone. The retail sector is North America’s largest employer, accounting for over 15 million workers, and in an industry continually challenged for profitability, the potential upside of replacing workers with technology has to be tantalizing.

So, are people now truly an endangered species in retail? Will technology displace retail workers the way steam-powered machines displaced horses in the 18th century? The answer is neither as simple nor definitive as you might think.

A recent study out of Oxford University examined the likelihood of different types of workers being replaced by technology and determined that there is a 92% probability of retail labor being displaced over the coming decade. There are several reasons for this.

The first is that most retail workers are dreadfully underpaid. In the U.S. for example, the median wage for all retail workers in 2012 was $10.29 per hour or $21,410.00 per year. In the same year, the poverty threshold for a U.S. family of four was set at $23,492.00. In other words, for at least 50% of retail workers, supporting a family with a spouse and two children on a retail salary, implicitly means living in poverty.

Diminishing Return on Wages

While you might think such low wages would serve to insulate retail workers from technological disruption, it actually makes them much more vulnerable. Here’s why. While the Federal minimum wage is set at $7.25 per hour and some states have minimums slightly above that, most estimates suggest that if minimum wage had kept pace with inflation, it would currently be set at or above $20.00 per hour. This wage chasm presents tremendous problems for both retailers and their employees. If a retailer raises wages from $7.25 per hour to $7.75 per hour, it represents a significant (6%) increase to payroll. However, even at $7.75 per hour, an employee’s earnings still fall horribly short of the $20.00 per hour they would be receiving if wages were properly indexed to inflation in the first place. This remaining shortfall results in unmet expectations for the employee, even lower morale, reduced performance and ultimately diminished returns for increase for the employer. Each incremental increase in wages only perpetuates a downward spiral in performance and dissatisfaction. In the end, it’s this conundrum that makes an investment in technology to replace workers look more attractive to a retailer than making an investment in the workers themselves. It may not seem morally right but it’s financially true.

Secondly, while few professions are immune to technological disruption, retail workers are particularly at risk because much of their work has been reduced to a series of manual, repetitive tasks. Their core work has to do with looking up prices, checking inventory levels, scanning packages and transferring bits of product information from a manual or database to a customer. Unfortunately, this also happens to be just the sort of work in which technology far exceeds human capability.

The Problem With Robots

But all this is not to say that we will soon be living in a dystopian future, devoid of people. Robots aren’t perfect either. In fact, there have been some extremely compelling studies that clearly show that robotics and cognitive computing power alone are often not the best solutions to complex problems.

For one thing, robots tend not to have very good fine motor skills, making the manipulation and demonstration of complex objects very difficult and slow. Meanwhile, artificial intelligence is great at retrieving factual data and solving linear problems but not so adept at intuiting creative and sometimes lateral solutions, much less forging an emotional connection with a customer. Technology, on its own, tends not to be the optimal solution.

“Welcome to the age of augmented humanity.”

– Eric Schmidt, Google

To the point, in his 2014 book, Smarter Than You Think, author Clive Thompson discusses what became an ongoing argument within chess-playing circles about which is more dominant at the game – human beings or chess-playing software. Thompson writes:

In 2005, there was a “freestyle” chess tournament in which a team could consist of any number of humans or computers, in any combination. Many teams consisted of chess grandmasters who’d won plenty of regular, human-only tournaments, achieving chess scores of 2,500 (out of 3,000). But the winning team didn’t include any grand masters at all. It consisted of two young New England men, Steven Cramton and Zackary Stephen (who were comparative amateurs, with chess rankings down around 1,400 to 1,700), and their computers.

Why could these relative amateurs beat chess players with far more experience and raw talent? Because Cramton and Stephen were expert at collaborating with computers. They knew when to rely on human smarts and when to rely on the machine’s advice. Working at rapid speed—these games, too, were limited to sixty minutes—they would brainstorm moves, then check to see what the computer thought, while also scouring databases to see if the strategy had occurred in previous games. They used three different computers simultaneously, running five different pieces of software; that way they could cross-check whether different programs agreed on the same move. But they wouldn’t simply accept what the machine accepted, nor would they merely mimic old games. They selected moves that were low-rated by the computer if they thought they would rattle their opponents psychologically.

In essence, a new form of chess intelligence was emerging. You could rank the teams like this: (1) a chess grand master was good; (2) a chess grandmaster playing with a laptop was better. But even that laptop-equipped grand master could be beaten by (3) relative newbies, if the amateurs were extremely skilled at integrating machine assistance. “Human strategic guidance combined with the tactical acuity of a computer,” Kasparov concluded, “was overwhelming.”

So, if Kasparov’s assertion is correct, it follows that the perfect retail sales associate is neither a human, nor a piece of technology but rather a human with a mastery of technology. Can we expect to see robots and artificial intelligence in retail stores? It seems inevitable. Will these technologies displace significant numbers of people? This too seems almost certain. But will they eradicate entirely the need for people in retail? It’s doubtful…for now at least.

The Retail Employee Of The Future

What’s certain is that the role of human retail workers is set to change vastly in the years to come. The retail salesperson of the future is more likely to be an engaging and charismatic brand ambassador, skilled in building rapport with customers but assisted in their work by a range of robotic, mobile and AI technologies that enable them to deliver extraordinary service. Unlike today’s retail employees, who I would argue often find themselves becoming slaves to technology, tomorrow’s retail workers will be the masters of it. Talented humans that manage the magic of the brand experience, while technology assists with the data-driven, repetitive grunt work.

Smart retailers will be those that recognize that the future of retail work is not a question of humans or great technology but rather great humans with technology.