By Doug Stephens

As consumers we are continually making trades, concessions and compromises in the quest to satisfy our needs and wants. According to Kevin Maney, author of the book Trade Off: Why Some Things Catch On and Others Don’t, there is a constant push and pull between what he calls fidelity and convenience. Fidelity being the quality of the experience associated with acquiring something and convenience, referring to the ease with which something can be acquired.

High fidelity experiences are usually less widely available and often cost considerably more. They tend to be more exclusive and offer a higher level of quality, shopping experience and service. Convenience based experiences are comparatively easy to find and cost less. They also tend to serve larger customer segments.

High fidelity experiences are usually less widely available and often cost considerably more. They tend to be more exclusive and offer a higher level of quality, shopping experience and service. Convenience based experiences are comparatively easy to find and cost less. They also tend to serve larger customer segments.

Consider the difference between a dinner at New York City’s famed Peter Luger steakhouse and your local McDonald’s. In a given week, the same consumer may choose to eat at both but for very different reasons. McDonald’s is a convenience driven choice, while the decision to go to Peter Luger is being prompted by the desire to have an exceptional dining experience. One is cheap and convenient and the other is expensive and high fidelity.

Both propositions have a place and can be very successful. Convenience serves our needs, while fidelity feeds our wants. As Maney puts it, we need convenience products but we lovefidelity products.

Companies hit pay dirt when they achieve Super Fidelity or Super Convenience, a place where they are literally untouchable in their chosen market space. Consider Neiman Marcus and Wal Mart; two brands that sit at opposite ends of the fidelity/convenience spectrum and yet both very dominant.

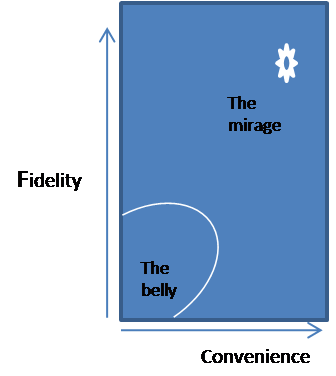

Between the two ends of the spectrum lies what Maney calls the belly – a zone where businesses are neither very convenient nor high fidelity but merely a little of both. This, he maintains is a perilous spot to be in. Consider Sears. Having neither the low prices nor the convenience aspects of a Wal Mart and also lacking the fidelity of a Saks Fifth Avenue, it has been relegated to the belly. On the fringes of the belly are the retailers that manage to maintain their positions but don’t necessarily enjoy dominance. This represents the majority of companies that fight it out in the trenches every day for an extra percentage point of market share. Every day is a struggle to avoid falling into the belly.

He also warns marketers against chasing what he calls the mirage, where companies attempt to become both super fidelity and super convenience – a combination he maintains is impossible to achieve. Pursuit of the mirage, suggests Maney, is precisely what led to Starbucks’ difficulties in 2007/2008. The very exclusive aura that surrounded their brand simply disappeared when suddenly there was a Starbucks on every corner, at every airport and in every grocery store. In pursuing super convenience, they severely diminished their fidelity.

What I like about Maney’s model is it’s simplicity compared to other such positioning frameworks. It’s something any business large or small can easily use to chart their current market position. It also serves to provide a clear compass heading for businesses to follow in improving that positioning.

According to Maney, if there is a consistent trait among great businesses it’s their ability to discover the thing they do better than anyone else and then focus relentlessly on doing it.