By Doug Stephens

Recovery is a word we hear a lot these days. It seems that each week experts sift through the tea leaves of economic indicators looking for even the faintest sign that the fabled “recovery” has begun. We’ve taken to measuring retail performance a week at a time in search of any positive sales data. Marketers continue to bait the consumer with discounts and promotions, hoping to get even a brief spike in foot traffic (regardless of the long-term impact on their brand). Wall Street applauds corporate cost cutting measures and layoffs with higher share prices, while secretly wondering how much further budgets can be cut in lieu of meaningful sales growth. Each day we wait and watch for the “bounce-back”.

The problem with monitoring the recovery in this way is that it is as short-sighted and speculative as the behavior that brought on the recession in the first place. Hinging decision-making on the basis of any shred of positive data is a recipe for disaster that fails to acknowledge the deep, underlying issues that led us to where we are now. This recession is like an oak tree, with tangled roots that stretch back decades and it will take time, hard work and some sharp tools to fell it.

Looking back to see the future

In order to really understand our current problem, we need to look back as far as the late 1970’s. It was then that many of the causes of our current situation were born.

I point here to some fascinating research conducted by attorney and law professor Elizabeth Warren. In what was an exhaustive study, she compared the relative household economic condition of the average American family (married with two children) in 1979 to the same family in 2005. All the data was meticulously scrubbed and adjusted for inflation. Some of the key findings were as follows:

- Throughout the period 1979 to 2005, the average personal income of men remained virtually stagnant.

- Any gains in household income were a result of entry into the workforce of another wage earner, often the female of the household.

- Whatever gross gains were made as a consequence of the additional wage earner, were generally nullified by the enormous escalation in the cost of living though that period, particularly in the areas of home ownership (+80-100%), child care (+100%), health insurance (+103%), automobile expense (+70%) and tax rates (+25%). This doesn’t even take into account 2005 costs that simply didn’t exist in 1979, such as cell phones.

The net result was that the average American family in 2005 was significantly further behind economically than the same family in 1979.

After paying for their basic needs, the average family had less money left over at the end of the day than they had almost 30 years earlier despite having more family members working.

This fact, however, seems completely incongruent with the level of consumption and spending that was taking place in most parts of North America throughout that period. Despite a few economic speed bumps along the way, consumerism was rampant, particularly from about the year 2000 on. If in fact, consumers had less discretionary income, then where was the money coming from to fuel this spending?

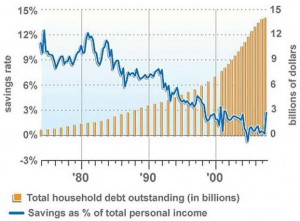

The answer lies in a leveraging of historic proportions that began in the 1970’s but really hit stride in the mid 1980’s. As the graph below indicates, throughout the period of 1970 to 2005, the average personal savings percentage went from 12.5% to negative 1%. Americans were banking twelve and a half cents on every dollar earned in 1970. They were spending a dollar and one cent of every earned dollar in 2005. By corollary, household debt outstanding grew to unprecedented levels.

And the leveraging didn’t end at the consumer. Institutions and governments were following the same course, running up dept and deficits the likes of which were never thought possible.

During the week of October 6, 2008 the entire house of borrowed cards collapsed and the consumer found themselves caught. Their investments declined, including in many cases their only real nest egg… their home; they had no cash in the bank and a mountain of unforgiving debt. And on top of it all they now had the added worry of job loss to contend with.

The uptick you see at the far right of the graph is the instinctive hoarding of cash that took place immediately following the declines on Wall Street and the collapse of several financial institutions, where personal saving rates rebounded and continue to rise even now. It’s that upward trend in savings that has had even the most aggressively discounting retailer scratching their head as to why their goods aren’t selling; the consumer is rebuilding their war chest. How long the savings rate will continue to push upward is unknown but a return to a double-digit percentage isn’t inconceivable.

The long road to recovery

What all of this amounts to is that the economy will only begin to heal in a real way when the average consumer feels decidedly less vulnerable and scared. This means a suitable amount of cash in the bank, relative job security and signs of sustained growth in the value of their investments and holdings. Until these things are firmly in place, any potential recovery will be stymied. It took decades to get into this situation. Recovery could take many years and be painfully gradual. There is simply no cogent arguement for a fast recovery.

For retailers the ultimate question is how to survive the waiting game. While there’s no single correct answer, there are a few broad realities worth paying attention to and developing strategy to address.

1. Reckless price cuts are not effective: Consumer spending has been squarely realigned to necessities until further notice. Simply lowering the price of non-necessities will have a very minimal impact on sales but may erode margins and brand image to the point of disaster for unwitting retailers.

2. Middle of the road propositions will fall flat: Bringing the consumer to spend on anything but necessities will call for remarkable propositions that either provide extraordinary value or extraordinary experiences. For example, Apple concluded a record sales year in 2009 – the height of the recession – by providing consumers with high perceived value that they felt couldn’t get elsewhere.

3. Baby Boomers are receding as consumers: According to the Bureau of Labor statistics, consumer spending declines precipitously after the age of 50. The peak of the Baby Boomer generation is now 55 years old. So, the generation that fuelled record consumption is sidelined, due in part to the recession but also as a consequence of their natural dénouement as consumers.

For this reason, retailers will have to capture new market share among younger age cohorts or pry Boomer market from competitors by addressing their evolving needs more effectively.

4. Generation Y are not their parents: Many are holding out hope that Generation Y will be the catalyst for recovery. It’s true that this is a huge generation that has a solid track record for spending but they’re also different in almost every respect from their parents’ generation. Only those retailers who truly understand and respond to their unique needs and preferences stand a chance of engaging them as consumers. The old rules of retail no longer apply.

Knowing all this isn’t likely to make you feel much better about our current situation but if nothing else perhaps it lends a perspective based in reality as opposed to blind optimism – although I’m hoping for the best just like everyone else. Perhaps with a keener understanding of the root causes of the current consumer paralysis we can market and retail with a greater degree of empathy and ultimately speed the process of recovery.