Review any retail sales training program written in the past 50 years and you’ll likely encounter multiple references to the word “rapport”. Rapport, or the relationship and understanding between people that builds trust and confidence, has long been regarded as a vital aspect of effective selling. The idea is that in order to properly assess and address the needs of the consumer, the salesperson has to be able to fundamentally relate to those needs. Then and only then, the theory asserts, can salespeople recommend the best product, from personal experience, to satisfy the customer’s needs, with credibility. In other words, the more alike the lives of the customer and the sales associate are, the easier it is to build rapport.

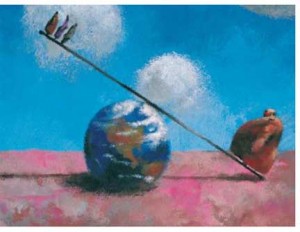

Over the past 30 years however, the economic distance between the lowest paid Americans (many of whom are frontline retail workers) and the highest paid, has been widening at an alarming rate. The likelihood that retail workers are serving someone outside their economic bracket is escalating. In fact, a recent study showed that a mere 5% of all consumers now account for at least 37% of all consumer outlays. Contrast this with the 80% of income earners below them who only amount to only 39.5% of consumer outlays and the problem presents itself quite clearly. The retail sales associate of today earning a national median hourly wage of $9.94 per hour, is less similar to their customer (from a socioeconomic standpoint) than they have been in more than 100 years.

It wasn’t always this way

Incomes in America have not always been so divergent. In fact, through the 1930’s and 1940’s income distribution actually improved. Through the boom in growth in the 1950’s and 1960’s the spread between the lowest and highest earners remained stable. It’s the period from 1979 to the present that writer Timothy Noah refers to as the “Great Divergence”.

Noah points out that in 1979 an individual in the top 20% of all income earners had an income 8 times that of someone in the bottom 20%. By 2007 the ratio had risen sharply to 14 times. Similarly, the ratio between the middle 20% and the bottom 20% also increased, from 3 times greater in 1979 to 4 times greater in 2007.

The causes for the inequity are varied and fervently debated. Political and taxation policy, foreign trade, the decline in the power of labor unions, the premium paid to college educated workers and blatant inequities in CEO and executive compensation and incentives have all been implicated to varying extents for the growing imbalance.

This expanding chasm between the lowest and highest paid in American society raises obvious concern from a social standpoint but also presents significant challenges to businesses attempting to design and deliver a premium service experience through their frontline retail staff – many of whom may be living near or below the poverty line.

For this reason, retail has largely ceased to be regarded as a career and instead is seen by many to be a mere stopping point on the way to something better. This in turn has contributed to epic turnover in the industry and presented issues for retailers attempting to train and retain their best staff.

Keeping Up

Beginning in 2007, Washington began to make small upward adjustments to Federal minimum wage, which stood at $5.15 for the previous ten years, taking it first to $5.85, then to $6.55 in 2008 and finally to $7.25 in 2009, where it remains today. It’s hard to dispute the significance of the increase on a percentage basis and yet many argue that this figure still woefully lags 30 years of cumulative inflation and should in fact, be somewhere well above $10.00. Despite the math, roughly half of the nation’s frontline retail workers earn less than $10.00 per hour. Which raises the question, how can a retail sales associate relate to the consumer who may be spending more on pair of pants than the sales associate themselves will gross that day?

Despite the escalating tension the income gap creates, approaches on the part of retail companies have remained relatively uncreative over the last 30 years. Programs aimed at better hiring, increased training and commissions in lieu of base pay have all been relatively standard responses. None of these truly address the issue of retail employees who are losing economic and social ground, leaving them vulnerable in an increasingly volatile economic landscape.

To be fair, there are industry exceptions. The Container Store, for example, claims to pay its employees a rate between 50 and 100% better than industry averages. They also choose to disregard pre-defined wage scales or caps and instead place emphasis on individual merit and performance.

Online retailer Zappos takes a slightly different approach, paying its frontline call center employees slightly below average base wages but providing a benefit package, including 100% paid health care and paid time off, which substantially exceeds industry norms. The result is a total compensation package that delivers a greater total value. This is in spite of the fact that only 25% of Zappos customer interactions come via their call center. It’s these personal, live human interactions however, that Zappos leadership regards as important moments of truth for the brand and is thus prepared to invest accordingly.

It’s worth noting that both The Container Store and Zappos consistently rank among the nations top retail companies by both customers and employees alike.

Getting beyond money

This is not to imply that wages and benefits alone deliver employee satisfaction. There’s ample research to suggest that true employee satisfaction is driven by more intrinsic stimuli such as recognition, belonging, autonomy and sense of purpose. However, when wages are so low that even basic needs like housing, education and nutrition can’t be met, other more existential needs become moot. According to Daniel Pink, author of the book Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, companies need to pay their people at least enough to take “the problem of money off the table.” This may be a different figure for every employer. But until they do, Pink suggests, it will remain a preoccupation and a deterrent to performance.

A Business Problem

Stripping the social and political sentiment out of the question and looking at the issue of retail wages purely from a business standpoint may provide at least some clarity.

The question for all businesses including retailers may actually be quite simple. If people (the people in their stores) truly represent their greatest competitive advantage and the critical medium through which consumers experience the brand, then business expenditure and investment should be guided accordingly. Furthermore, if the goal of the business is not only to compete but to dominate the human brand experience, then it must ignore minimum wage guidelines and target instead a rate of pay and package of compensation that begins (at least incrementally) to bridge the social and economic gap between staff and the customers they serve.