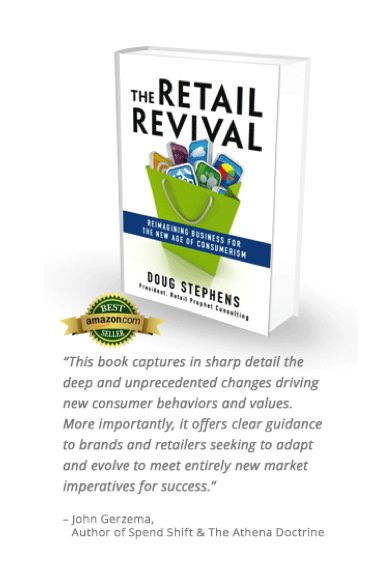

By Doug Stephens

Sharing is getting a lot of attention and for good reason. Uber now has more drivers in New York City than Yellow Cabs. AirBNB will put more people in rooms this year than Hilton Hotels. Everything from bicycles to private jets is being shared, as growing numbers of consumers eschew permanent ownership in favor of occasional usage.

Today, the burgeoning sharing economy amounts to more than 3.5 billion dollars and is estimated to balloon to ten times that number by 2025. However, despite these astonishing projections, many analysts remain skeptical, characterizing the rush to sharing as a mere knee-jerk reaction to the Great Recession and a behavior driven largely by unemployed, underemployed and debt-laden Millennials. New York Magazine’s Kevin Roose went so far as to write that the sharing economy was more a sign of economic “desperation” than anything else; a new fad sure to be quashed upon full economic recovery.

But contrary to how it may seem, this tendency toward collective consumption isn’t new at all. Just the contrary; it’s hundreds – if not thousands, of years old, stretching back to a time when cities were smaller, communities were intrinsically more connected and goods were comparatively more expensive. It wasn’t uncommon for farmers who owned a particular piece of equipment to willingly share it with neighboring farms. In return, they too would borrow from friends and neighbors as necessary to meet their needs. Even human work capacity was shared, as those farmers with labor to spare would offer a hand to those who needed it, with the expectation of a returned favor if and when the need arose. Together, friends and neighbors maximized the utility of both the things they owned and the work capacity they possessed. Not only did these small, informal, sharing economies make good sense, they could be easily formed on foundations of personal connection, mutual trust and common interests.

The Industrial Devolution

With the advent of the Industrial Revolution, however, things changed. Cities grew, manufacturing scaled, and the cost of production decreased exponentially making individual ownership of goods more attainable. Most importantly though, the tight connection that once existed between neighbors within communities frayed and the bedrock of trust on which small rural sharing economies were founded began to slowly crumble. If you no longer knew the people you lived near, how could you lend them your possessions? If you didn’t feel somehow mutually connected, why would you spare your time or efforts to help them?

By the mid-twentieth century, individual ownership of goods was not only the norm but was steadily becoming a pre-occupation with many consumers. As the modern middle-class came into existence, ownership and accumulation of goods became the aspiration of an entire generation of post-war consumers. Sharing was all but dead.

The Great Reconnect

Ironically, by the mid-2000’s it was technology that began to bring society back together; in effect, repairing the social disconnects it had catalyzed only a couple of generations earlier. Digital technology made it easier for communities to reconnect and for members of those communities to establish trust based on collective values. Social networks have allowed people with similar values, interests and needs to easily self-identify and come together. In short, communities, cities and even the globe have begun to feel smaller again.

One of the results of this regained level of social connectivity is the return to  sharing. From an economic and environmental standpoint sharing has always made sense, but today – after a two hundred or so year hiatus – it’s once again possible to establish the fundamental human connections to facilitate it.

sharing. From an economic and environmental standpoint sharing has always made sense, but today – after a two hundred or so year hiatus – it’s once again possible to establish the fundamental human connections to facilitate it.

So, despite what naysayers might believe, there’s little evidence to suggest that the sharing economy will simply vaporize with economic recovery. In fact, I would argue that history will likely view our departure from sharing, not our return to it, as the only anomaly.